Mind

Has Mountains

by

Julian Cooper

with additional illustrations for the web.

When

a piece of land inclines toward the vertical our relationship towards

it changes. We can no longer walk on it and it cannot grow food for us.

So we either ignore it or it becomes an aesthetic object in itself, akin

to a work of art, or as a visible record of time and weather and geological

change.

When

a piece of land inclines toward the vertical our relationship towards

it changes. We can no longer walk on it and it cannot grow food for us.

So we either ignore it or it becomes an aesthetic object in itself, akin

to a work of art, or as a visible record of time and weather and geological

change.

I've been looking closely at mountain and rock faces for a long time, sometimes in the course of climbing them or imagining a route up, but more often reading them as surfaces that parallel the surface of possible paintings that I might like to make.

Built-up deposits, erosions through time and weather, gravity making itself felt in water traces and landslips or avalanches, accretions of layer through time and process, the ground of rock and earth showing through in places, all have their counterparts in paint-language, and so I find the act of painting a mountain face largely a form of translation from one vertical surface to another, with the possibility of making a kind of music out of the articulation of the paint, and out of the internalisation of something that is 'other' or maybe out of finding whatever is in common between a mountain face and a person. When the land is vertical and it is no longer the ground we walk on, it is open to us to view it as a kind of complex being, like us in some respects, with a 'face'.

...

...

Mountain form usually shows self-similarity from the large ridges down to boulders and stones, I try to re-create this compelling, almost hypnotic quality, by being faithful to the topography of the mountain and not trying to force an egotistical or mystical image upon it, realising it as field of causality and interdependence, almost an emblem of interconnectedness, so that say a patch of snow is a particular shape due to the form of the rock on which it lies, and the shape of sunlight on that snow is as a result of the angle of the sun in relation to that terrain combined with the shape of rock casting its shadow.

With

the help of a Northern Arts grant I went to the Kanchenjunga region of

Nepal in the late autumn of 1999, accompanied by long-time climbing partner Alan Howard, who helped set

up the arrangements through a sherpa he knew from past trips. The idea

was to continue pursuing a lead I'd begun on a similar painting expedition

to the Peruvian Andes in 1995, where I had carried 7ft x 5ft canvasses

up to high positions opposite big mountains and worked on them on site.

Painting in front of the mountain, I'd found, had a limiting effect as

well as being stimulating; the sheer mass of information in front of me

coupled with uncertainties of weather and time meant that I didn't get

under the surface of the subject in the way I had hoped.

accompanied by long-time climbing partner Alan Howard, who helped set

up the arrangements through a sherpa he knew from past trips. The idea

was to continue pursuing a lead I'd begun on a similar painting expedition

to the Peruvian Andes in 1995, where I had carried 7ft x 5ft canvasses

up to high positions opposite big mountains and worked on them on site.

Painting in front of the mountain, I'd found, had a limiting effect as

well as being stimulating; the sheer mass of information in front of me

coupled with uncertainties of weather and time meant that I didn't get

under the surface of the subject in the way I had hoped.

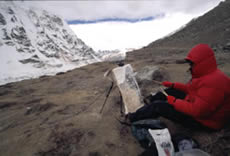

I

realised a better use for plein air painting is as a recording

device alongside the camera and the memory, and the real paintings could

be done better when I got back to my studio. In fact I discovered that

the studies were real paintings too, and the act of painting on site was

invaluable as a method of rehearsing and getting into my head various

strategies for converting what came through my eyes into paint on canvas.

I took a stock of small canvasses (20 ins x 30ins) and an aluminium collapsible

stretcher I had made, and I used a new water-soluble oil paint with my

camera tripod doubling as an easel.

I

realised a better use for plein air painting is as a recording

device alongside the camera and the memory, and the real paintings could

be done better when I got back to my studio. In fact I discovered that

the studies were real paintings too, and the act of painting on site was

invaluable as a method of rehearsing and getting into my head various

strategies for converting what came through my eyes into paint on canvas.

I took a stock of small canvasses (20 ins x 30ins) and an aluminium collapsible

stretcher I had made, and I used a new water-soluble oil paint with my

camera tripod doubling as an easel.

Kanchenjunga

at 28,208 ft is the world's third highest mountain after Everest 29,028

ft and K2 at 28,253 ft, and is in one of the most remote parts of the

Himalayas, nearly 2 weeks walk from the road head. It has always been considered

a difficult and dangerous mountain to climb, only about 100 people having

been to the summit so far since 1956, (or just short of the summit-George

Band and Joe Brown, the 1st ascensionists set the precedence of stopping

a few paces from the top, following the wishes of the Sikkimese). The

sight of Kanchenjunga from Darjeeling in the east was familiar to many

Europeans long before Everest was recognised as being a higher mountain.

I was interested in painting it from the north side, at the base camp

area called Pang Pema at around 17,000 ft. Because it was early December

by the time we got to Pang Pema it was getting wintry. Minus 20 degrees

outside at night, only 5 degrees warmer in the tent.

nearly 2 weeks walk from the road head. It has always been considered

a difficult and dangerous mountain to climb, only about 100 people having

been to the summit so far since 1956, (or just short of the summit-George

Band and Joe Brown, the 1st ascensionists set the precedence of stopping

a few paces from the top, following the wishes of the Sikkimese). The

sight of Kanchenjunga from Darjeeling in the east was familiar to many

Europeans long before Everest was recognised as being a higher mountain.

I was interested in painting it from the north side, at the base camp

area called Pang Pema at around 17,000 ft. Because it was early December

by the time we got to Pang Pema it was getting wintry. Minus 20 degrees

outside at night, only 5 degrees warmer in the tent.

The

weather held for 4 days and I got two paintings done after a bit of exploration, but the intended 10 days at base camp was cut short

by a 24 hour snow storm which sent us retreating 2 days down to a lower

altitude at Kambachen at around 14,000 ft where there were other parts

of the Kanchenjunga massif towered over the settlement. I painted them

in the remaining five days available, packing up to leave at the same

time as the few remaining herdsmen and their families were loading up

their yaks to spend the winter at lower altitudes. I came away with five

paintings, less than I had expected but very useful for the process of

making the bigger paintings in the studio.

a bit of exploration, but the intended 10 days at base camp was cut short

by a 24 hour snow storm which sent us retreating 2 days down to a lower

altitude at Kambachen at around 14,000 ft where there were other parts

of the Kanchenjunga massif towered over the settlement. I painted them

in the remaining five days available, packing up to leave at the same

time as the few remaining herdsmen and their families were loading up

their yaks to spend the winter at lower altitudes. I came away with five

paintings, less than I had expected but very useful for the process of

making the bigger paintings in the studio.

I also photographed as I painted, tracking the light through telephoto lenses as it hit the mountain at oblique angles, leaving deep pools of shadow on the steeper faces, having discovered that it was the view of the mountains through binoculars that interested me most, bringing me close to the unapproachable.

_med.jpg)

Chang

Himal, based on a study I did on site, is the first of the studio

follow-on paintings, but moving closer into the mountain so that the summit

is lost and the sky isolated into two shapes. It was important to have

established a ground layer of paint totally at odds with the eventual

surface layer; in this case the ground is a deep red oxide with fine sand

added to give tooth to the marks made by the brush.

Chang

Himal, based on a study I did on site, is the first of the studio

follow-on paintings, but moving closer into the mountain so that the summit

is lost and the sky isolated into two shapes. It was important to have

established a ground layer of paint totally at odds with the eventual

surface layer; in this case the ground is a deep red oxide with fine sand

added to give tooth to the marks made by the brush.

The

reason for losing the top of the mountain is to concentrate on the relationships

within the form of the mountain rather than between it and the sky, which

is a traditional Romantic formula. My ideal template is a field in which

things happen rather than the object isolated in space. It was most important

in this painting to see if I could re-create the image of sunlit snow

and ice ridges into tangible paint forms that have a life of their own,

not simply dependent on their descriptive function. Using thick opaque

paint for the light and thin transparent paint for the dark isn't just

an old rule of painting, it is also a direct physical analogue of the

way light either reflects off a surface or is absorbed by it. Quite soon

into this painting I discovered that I had to keep half-destroying the

image as I created it, otherwise it lost a feeling of reality or of being

a place-in-itself, and gravity had to be given a part in the making of

it.

The

reason for losing the top of the mountain is to concentrate on the relationships

within the form of the mountain rather than between it and the sky, which

is a traditional Romantic formula. My ideal template is a field in which

things happen rather than the object isolated in space. It was most important

in this painting to see if I could re-create the image of sunlit snow

and ice ridges into tangible paint forms that have a life of their own,

not simply dependent on their descriptive function. Using thick opaque

paint for the light and thin transparent paint for the dark isn't just

an old rule of painting, it is also a direct physical analogue of the

way light either reflects off a surface or is absorbed by it. Quite soon

into this painting I discovered that I had to keep half-destroying the

image as I created it, otherwise it lost a feeling of reality or of being

a place-in-itself, and gravity had to be given a part in the making of

it.

Patch

of Light followed on from the previous painting, cutting more

of the sky out and presenting the mountain face as a field in which various

forces are at work. The sun leaves the mountain by stages when it goes

down, and the temperature drops suddenly. I watched the various shape

changes happen through binoculars, noticing that it nearly, but not quite,

repeated the same repertoire each day. This is a painting about two different

time scales, the light and the mountain. In painting the shadowed part

of the face, I brought to bear memories of long hours spent climbing on

cold icy faces and gullies, wondering when it would ever end.

Patch

of Light followed on from the previous painting, cutting more

of the sky out and presenting the mountain face as a field in which various

forces are at work. The sun leaves the mountain by stages when it goes

down, and the temperature drops suddenly. I watched the various shape

changes happen through binoculars, noticing that it nearly, but not quite,

repeated the same repertoire each day. This is a painting about two different

time scales, the light and the mountain. In painting the shadowed part

of the face, I brought to bear memories of long hours spent climbing on

cold icy faces and gullies, wondering when it would ever end.

In

Headwall the view is closer still,  with

no sky visible at all. It is a much larger painting which envelopes the

viewer. As soon as I saw these flutings in the distance when walking past

the end of the glacier of a large mountain called Kambachen I knew this

was the sort of thing I was looking for. These baroque shapes are created

by the combination of snowfall, avalanche and the action of the wind,

and when I saw it, the late afternoon sun was gliding past, the high altitude

light reflecting colour back into the shadows off the surrounding hills.

In constructing the paint surface as a mountain face, I have to keep two

opposing images simultaneously in mind, on the one hand the landscape

of paint a few inches away, on the other the illusion of snow, rock and

ice perhaps a mile away. I want the viewer to be aware of both, near and

far.

with

no sky visible at all. It is a much larger painting which envelopes the

viewer. As soon as I saw these flutings in the distance when walking past

the end of the glacier of a large mountain called Kambachen I knew this

was the sort of thing I was looking for. These baroque shapes are created

by the combination of snowfall, avalanche and the action of the wind,

and when I saw it, the late afternoon sun was gliding past, the high altitude

light reflecting colour back into the shadows off the surrounding hills.

In constructing the paint surface as a mountain face, I have to keep two

opposing images simultaneously in mind, on the one hand the landscape

of paint a few inches away, on the other the illusion of snow, rock and

ice perhaps a mile away. I want the viewer to be aware of both, near and

far.

If

I don't have a very strong model in my head of the three dimensional form

of each small section of mountain when actually applying the paint with

the brush, I end up with meaningless marks of paint, so in sense each

stroke or flurry of marks is a mental construct communicated into paint

through the arm and hand. I use long-handled brushes that need the involvement

of much more of the body than conventional brushes, so there is a greater

potential power behind the brush marks, and control is always in doubt.

Although the figure is absent from most of these paintings, I think that

it is implicit in the way they are made, the figure having been absorbed

by the ground.

If

I don't have a very strong model in my head of the three dimensional form

of each small section of mountain when actually applying the paint with

the brush, I end up with meaningless marks of paint, so in sense each

stroke or flurry of marks is a mental construct communicated into paint

through the arm and hand. I use long-handled brushes that need the involvement

of much more of the body than conventional brushes, so there is a greater

potential power behind the brush marks, and control is always in doubt.

Although the figure is absent from most of these paintings, I think that

it is implicit in the way they are made, the figure having been absorbed

by the ground.