UNFIXING EARTH-BOUND ROOTS

Whether it takes the form of a dark, mysterious entanglement beyond the safety of the town, asimagined by the Brothers Grimm; the lawless, sylvan refuge inhabited by Robin Hood; or the space of liberty and retreat into nature as founded in Thoreau’s Walden, the forest is a prevalent and powerful signifier throughout culture.

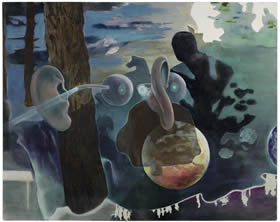

These latest paintings by Paul Hamlyn are set in the vast pine woodlands of Rendlesham Forest in Suffolk. Googling this location soon tells us that it is famous in some circles as the site of one of Britain’s ‘most significant military-UFO incidents’. That this forest should have a reputation which sets online UFO spotters atwitch is quite apposite to Hamlyn’s work. When the informal studies from nature that Hamlyn makes there are taken back to the studio in London all sorts of strange and unexpected narratives begin to emerge as he paints his way through into a parallel world where conventional logic and physical laws no longer apply.

In one sense, Hamlyn works within a very English tradition of landscape painting. Initially he makes loosely painted studies plein air, carrying his painting kit out into the landscape like some modern day version of his East Anglian ancestors Cotman and Constable. However, the larger studio works that follow suggest that not all is so green and pleasant in this landscape. In Mission for example a stylised skyline comprising art deco-like clumps of forest fans out in the distance. In front of this, the simplified silhouette of a boxy car suggests we read the thick horizontal line it sits on as a road, while in the foreground a dog squats to deposit a turd on the ground. Behind the dog a dark silhouette of a figure, one of the ubiquitous ‘walking shadows’ that populate Hamlyn’s work reaches out what could be a white-gloved arm. The most shocking thing about the picture however, is the realisation that what look like thick tree trunks converging upwards from in front of the ‘road’ are actually the smoke trails of missiles in flight. So the painting potentially describes a narrative that moves from the waste and dirt on the ground up through the man-made world and the nature that it erodes to the high-tech weaponry that is on its way to blast some distant target back into waste and dirt on the ground.

But any narratives in Hamlyn’s work are never so finite and resolved. A second reading, for example, may be that the figure is some kind of launch operative and that the missiles are the ones he has just despatched to the landscape scene that has been juxtaposed with its oncoming destruction. In this way the elements in the painting take up multivalent functions that subtly allude to all sorts of strange and sinister themes. These multiple narrative loops are brought to life through Hamlyn’s use of a montage technique that imports found images into the reworked scenes from the forest. But this is not the kind of montage that combines disparate objects and wide-ranging references in the way that artists such as Sigmar Polke or David Salle might do. His is a strategy that works by making the tentative suggestion that the elements in the painting, by the way they almost hang together, could actually form a coherent narrative. However, just as the viewer might be getting tempted by this option, any potentially coherent strands of meaning are displaced by other possible readings and the cycle begins again. We find ourselves caught up in ultimately indeterminate narrative structures which offer variable interpretations and are punctuated by false starts and dead-ends.

This effect is heightened by Hamlyn’s use of visual non sequiters such as gestural brush marks on the surface and shifts of context that break the option of reading the montage as the depiction of a single, continuous scene. Take the meandering, almost decorative border at the bottom right of Picnic for example. On closer inspection we see it actually consists of an inverted parade of small, silhouetted human figures that offer the possible reading that everything else in the painting is actually the upside-down part. Devices such as this are typical in Hamlyn’s work and serve the purpose of undermining any temptation to try and read the image as representing a believable, physical reality and serve to extend the possibilities of interpretation in these strange, heterogeneous worlds he presents. This effect is heightened by Hamlyn’s use of visual non sequiters such as gestural brush marks on the surface and shifts of context that break the option of reading the montage as the depiction of a single, continuous scene. Take the meandering, almost decorative border at the bottom right of Picnic for example. On closer inspection we see it actually consists of an inverted parade of small, silhouetted human figures that offer the possible reading that everything else in the painting is actually the upside-down part. Devices such as this are typical in Hamlyn’s work and serve the purpose of undermining any temptation to try and read the image as representing a believable, physical reality and serve to extend the possibilities of interpretation in these strange, heterogeneous worlds he presents.

Antecedents of this technique can be found, to cite just two examples, in the neurotic tableau of Max Ernst or the sketchy juxtapositions employed by René Daniëls, but to trace the work to these roots would be to ignore the overarching quality of Hamlyn‘s work which is it’s inescapable ‘Englishness’. This is due in part to a stylistic debt to English predecessors Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Victor Willing. Hamlyn’s work shares their emphasis on line, the thinly-painted secondary to tertiary palette and their loosely handled but restrained method of application. But the Englishness of Hamlyn’s work also owes a great deal to notable English bastions of oddness such as Edward Lear and Vivian Stanshall (if anyone reading this has never heard of him, he was the singer in a 60s group called the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, which tells you pretty succinctly where he was coming from). This manifests itself here in the form of a slightly eccentric feel to the paintings that is underpinned by a very dry sense of humour. A tongue-cheek quality is added to the playing out of narratives that engage serious themes and we feel in these paintings that we might be looking at something out of an old Quatermass movie that employs special effects improvised by an amateur inventor in a suburbangarden shed.

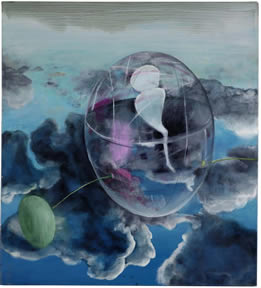

In Flight for example, some kind of transparent pod containing a spatula-like, tapering form is umbilically linked to what looks like a green egg. The image, with it’s rich turquoises and pinks, has the quality of an illustration for a science fiction book jacket or even something of the 1970s Prog rock album cover to it. Once again we are presented with multiple options as to how we interpret this image. As well as its sci-fi connotations, we could be looking at a close up of something from the natural world, a possibility heightened by the upside-down clouds in the background which suggest it could be sitting on a reflective surface such as water. But the scale is uncertain - are we looking at a giant alien being or the spawning ritual of a tiny insect? Is it possibly the creation of a crackpot scientist or the product of some chemically enhanced fantasy? This openness of interpretation serves to make any reference to the scientific in the work one that is rooted in the supernatural and fantastic rather than the logical and rational. Significantly this ambiguity of interpretations gives rise to one of the most powerful qualities of Hamlyn’s work as it also creates an ambiguity on the part of the viewer regarding potential responses. When looking at these paintings we find ourselves in the uncomfortable state of feeling that what’s going on in them could be simultaneously comic and horrific.

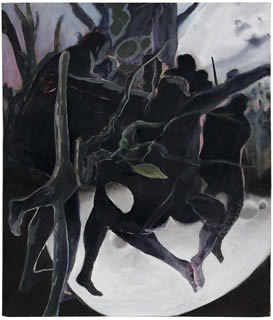

Certainly, some of the works do have an overtly sinister aspect to them. The Long Night has the feel of something out of the horror stories of H.P. Lovecraft and provides a glimpse into his ‘terrifying vistas of reality’ that according to Lovecraft could open up just beyond the sanctuary of the everyday world. The painting creates an unsettling impression as a dark group of figures seem to morph out of, or possibly in to, the surrounding forest in a violent tumult or perhaps some occult bacchanal. Hamlyn forces us into one of his ubiquitous double-takes as we realise that what looks like a semi-circular highlight beneath this anthropomorphic mass is actually a view of a moon seen in some NASA-enhanced close view. Suddenly we are in uncertain territory as to how to read this image as what we considered to be the ground suddenly becomes a view of outer space and we feel the same jolt as if taking a phantom step when the ground falls away before us in a dream. Certainly, some of the works do have an overtly sinister aspect to them. The Long Night has the feel of something out of the horror stories of H.P. Lovecraft and provides a glimpse into his ‘terrifying vistas of reality’ that according to Lovecraft could open up just beyond the sanctuary of the everyday world. The painting creates an unsettling impression as a dark group of figures seem to morph out of, or possibly in to, the surrounding forest in a violent tumult or perhaps some occult bacchanal. Hamlyn forces us into one of his ubiquitous double-takes as we realise that what looks like a semi-circular highlight beneath this anthropomorphic mass is actually a view of a moon seen in some NASA-enhanced close view. Suddenly we are in uncertain territory as to how to read this image as what we considered to be the ground suddenly becomes a view of outer space and we feel the same jolt as if taking a phantom step when the ground falls away before us in a dream.

The delicate balance that holds these images in a fragile equilibrium and offers the viewer so many ways into them is what makes these paintings so engaging. They don’t need to worry about trying to be ironic or self-regarding and are not afraid to take on dark and difficult themes. They sit at a point where painting gets interesting by pushing our thinking and messing with our heads more than just a little.

Andrew Child |